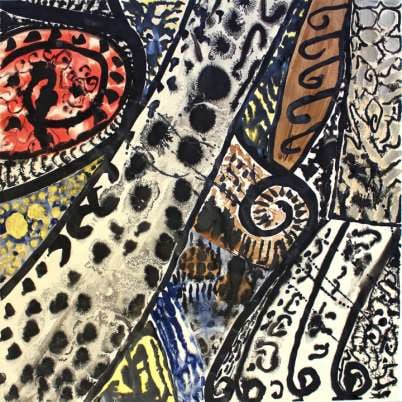

Sonja Sekula, Ethnique, 1961, gouache on paper, 20 1/8 x 20 1/8 inches (51.0 x 51.0 cm)

Sekula was part of a number of different overlapping scenes, and she was loved and thought highly of by many. And then nearly everything about her and her work got forgotten.

Sonja Sekula (1918-1963) piqued my curiosity when I first saw some of her works just a few months ago. Still, I was not sure what to expect when I went to the current exhibition Sonja Sekula: A Survey at Peter Blum Gallery (April 21 – June 24, 2017). I had known that this troubled, Swiss-born artist was part of an international circle of artists, writers, choreographers, and composers in New York in the 1940s, when she was in her early twenties, and that since her death by suicide in 1963, she and her work have largely been effaced from history. But aside from a few biographical facts and the handful of works I saw, I knew little else, but it was more than enough to bring me back.

At one point, while circling the galleries two space for the second or third time, I stopped to peer into a vitrine and saw photographs of a young woman sitting in the apartment of Andre Breton when he lived in New York during World War II. In another photograph she and sister are hugging Frida Kahlo, who is recuperating in a New York hospital room. There is a letter and drawing she sent to John Cage and a postcard she sent to Joseph Cornell. There is a photograph of a costume that she designed for Merce Cuningham, and an announcement for her show at Peggy Guggenheim’s Art of This Century in 1946.

Sekula and her family relocated to New York from Lucerne, Switzerland when she was a child. She lived in New York, New Mexico, Mexico, and in different cities in Europe. She was friends with Gordon Onslow-Ford. She fell in love with various women, including the Mexican artist and poet Alice Rahon, who had once been married to Wolfgang Paalen. Some of her work seems to reflect her knowledge of Onslow-Ford and Paalen, who, along with Lee Mullican formed the short-lived Dynaton group, and offered another path to abstraction. Sekula was part of a number of different overlapping scenes, and she was loved and thought highly of by many. And then nearly everything about her and her work got forgotten. Sekula’s last show in New York was at the Swiss Institute in 1996. There was an extensive catalog, but nothing seemed to happen. Perhaps the current exhibition will stir up a wider interest. It certainly would in a just world.

The works are dated 1942 to 1963, the entirety of her short-lived career. Sekula, who never worked big, also never became a gestural or a geometric painter, but this is also true of Charles Seliger (1926 – 2009), an artist who was also given his first solo show by Peggy Guggenheim at Art of this Century in 1945, a year before Sekula. Although they were both influenced by Surrealism and associated with Abstract Expressionism, neither of them fit the profile of the macho painter using a loaded brush or working on a large, post-easel scale. As the work of Thomas Nozkowski proves, orginality has nothing to do with scale and production costs, that these measures are capitalist myths.

Discussing the exhibition Abstract Expressionism, the first in-depth look at that movement to be mounted in England since 1959, which he organized for the Royal Academy in London (September 24, 2016 – January 2, 2017), David Anfam said: "Now is the moment to see its breadth and depth afresh. It’s an art of enormous ambition and originality, with which we need to reckon once more."

In Sekula’s case, the delicacy of her line and her tendency to section the surface into separate areas or, in some cases, compartments, connects her to another Swiss artist, Paul Klee, and to paintings of his such as “In the Current Six Thresholds” (1929), which is in the collection of the Guggenheim Museum, New York. At the same time, while Klee might have been an influence, Sekula made that influence into something all her own.In the early painting “Natica” (1946), she divides the horizontal canvas into a field of different-sized diamonds, rectangles, semi-circles, triangles, and irregular geometric forms. Through this field she draws a variety of colored lines, which may outline a form, or gather a number of them together to become a diagonal plane. “Natica” is an all-over geometric painting in which no form seems to be repeated. The predominant colors are shades of dark blue, giving a nighttime feel, interrupted by somber reds, lime greens, and a few yellows. I don’t how many paintings Sekula did in this vein, but “Natica” holds its own with Lee Krasner’s “Little Image” paintings, which she worked on from 1946 to 1950. She is a decade younger than Krasner.

After she began showing at Betty Parsons, Sekula did not try to fit in. She did works on paper and did not enlarge her scale. If anything, she seemed unable to accommodate herself to the world around her.

According to the biography included in the Swiss Institute catalog:

In April of 1951, the day after the opening of her third exhibition at Betty Parsons, she suffers a breakdown and has to be taken to the psychiatric clinic of the New York Hospital in White Plains by Manina Thoren and Joseph Glasco.

For the rest of her life, until she hanged herself in her studio in Zurich, Switzerland, at the age of forty-five, Sekula went in and out psychiatric hospitals, in both America and Switzerland. Despite her suffering and feelings of isolation, she made many distinctive works, as this exhibition conveys. In “Untitled” (1958), which is done in oil, graphite, and sand on cardboard, she makes a lattice of black lines, which are drawn horizontally, vertically, and diagonally. Some of the lines do not extend all the way across to the nearest vertical. The lattice begins on both the right and left sides of the composition and extends toward the center, which is dominated by a black, vertically oriented abstract form with a narrow vertical crevice visible in the upper half. That crevice gives the form volume, makes it a thing rather than just a shape. The thickness of the lines squeezes the spaces between them. The feeling is claustrophobic, and one senses that the thing (or life force) is trapped. All of this is conveyed formally; there is nothing overtly expressionistic about her work.

In this and other works done around this time, Sekula is out on her own: her work does not fit in with Abstract Expressionism, Minimalism, Color Field painting, nor the movement towards what would become known as Pop Art. And yet, she is not looking back, not reviving a pre-modern approach. That alone is reason to look again. We have to begin to discover what is urgent and original in her work, just as we did in the 1980s with Forrest Bess, another artist who showed with Betty Parsons.

Sectioning the surface, as she does in many of her works, suggests that compartmentalization was rooted in her psyche. So while she might not have attained a signature style, there are a number of formal preoccupations running through her work. Perhaps these preoccupations are connected to a statement she made in a journal entry: “1957: I do not feel part of any country or race.” At a time when we seem to be preoccupied with identity and nationality, Sekula’s statement speaks to those who feel that they belong to nothing and nowhere. As her writing makes clear, examples of which are included in this exhibition, she never overcomes her sense of displacement and isolation. It is not a social loneliness she endures, but one that afflicts the bones of her being.

As she wrote in a long run-on sentence that can be seen in the gallery, “The heart is a bit sad on all four corners, when it’s such a clear fall day in the middle of summer and all is wide open + you hear that…” Sekula did not always possess the ability to shut out the world, and that her senses and the associations they stirred up gave her extreme vertigo. Sekula’s center did not hold.

Years ago, I had the opportunity to sit next to Lee Krasner, while she was having lunch with Barbara Rose, Rosalind Krauss, Gail Levin, and other art historians. At one point, disgusted by the tenor of the conversation, she said: “You are just waiting for me to die so you can make your reputation.” Krasner had lived long enough to know that her work was going to be seen differently, even if she would not live long enough to see it happen. The recent reevaluation of Krasner’s status, as in Anfam’s exhibitions of Abstract Expressionism in England and America, gives a ring of truth to her pronouncement. Sekula is long dead. It is time to give her work a fresh look. I think we would be surprised by what we find there. I certainly was, and I have seen fewer than twenty works.

Sonja Sekula: A Survey continues at Peter Blum Gallery (20 West 57th Street, Midtown, Manhattan) through June 24.